Digital assets have been regularly spawning new cultural phenomena since the rise of the digital currency Bitcoin in 2010. Following tokens made as a joke such as Dogecoin and Shiba Inu Coin—both cryptocurrencies that feature Shiba Inus as their “mascot”—non-fungible tokens (NFTs) in 2021 have become the cryptocurrency world’s latest hit.

And since the industry is not without controversy, particularly regarding its environmental impacts, some Lasallians have decided to take advantage of its issues to shed light on the same issues.

You get a monkey, you get a monkey, everyone gets a monkey

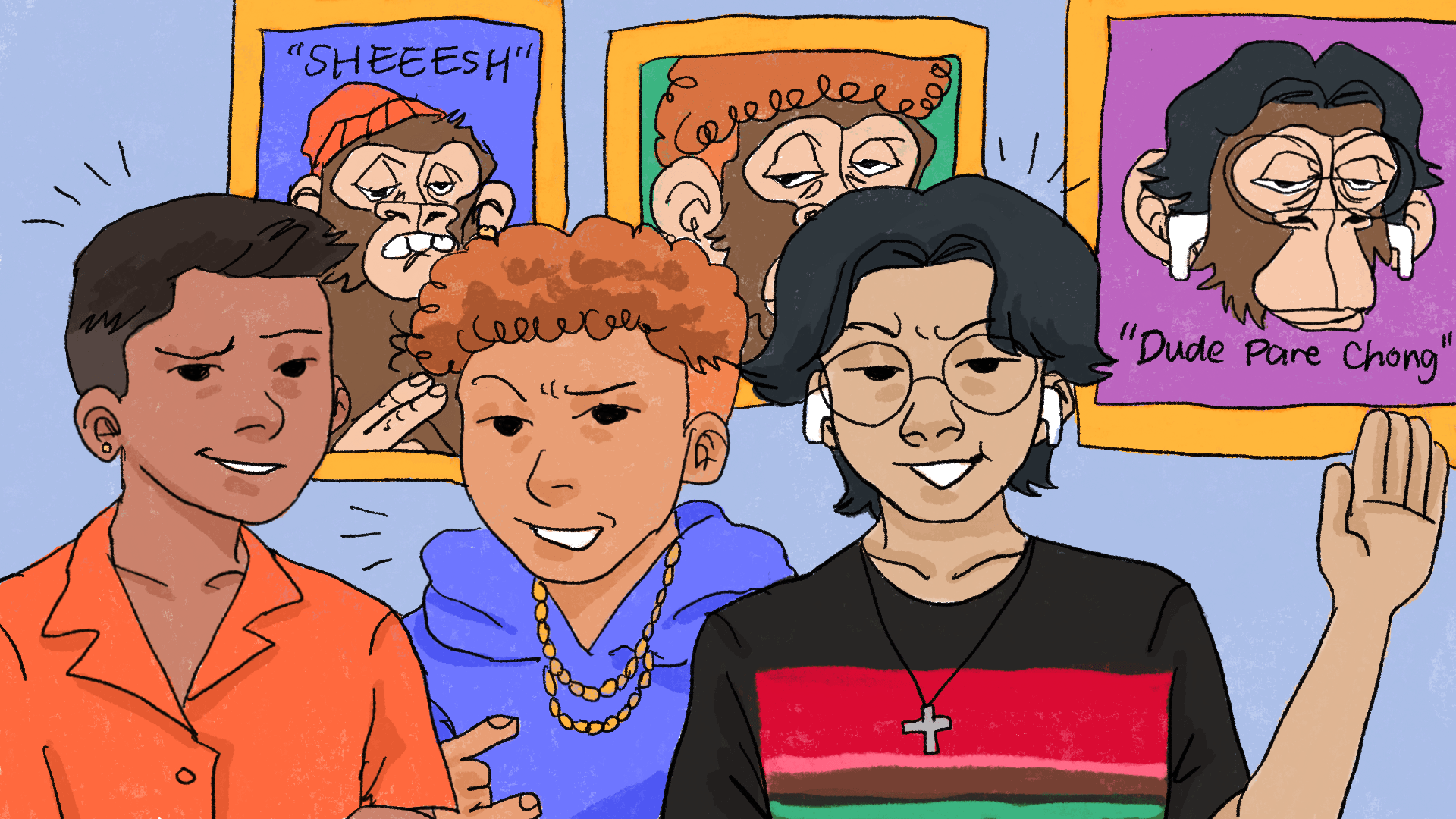

Students from the Gokongwei College of Engineering, College of Computer Studies, and Ramon V. del Rosario College of Business in March received the Elongated Muskrat Award for Dudebro Innovations for their groundbreaking advocacy work involving NFTs. Miguel Alfonso Broarez (IV, BSMSCPE), Juan Isaac Chua (III, CS-NIS), and Rafael Antonio Alargado (VII, ENT) were recognized for creating their own NFT collection, “The Ransomed Collective” (TRaCo), which features cartoons of various animals in a bid to promote the protection of the environment.

TRaCo features a number of NFTs with different and distinct animals, facial expressions, accessories, and clothing. Using a program that randomizes these layers to create unique variations, the group has minted at least 3,000 “conyo-fied” animals with more to come.

“We wanted to, like, you know, make you feel like you own an animal for real but without the hassle of making alaga it or getting in trouble with the gobyerno, you know?” Broarez explains. “I feel like that will help people become aware of why we need to help the environment, you know, you know?”

Broarez also comments that this would be a “good business model” and that it is “stonks, bro” but affirms that they are doing this for the environment.

Moreover, this works because whoever buys an NFT buys a digital certificate of ownership for each of TRaCo’s photos. Such a certificate grants them sole right to the original copy of a piece of art, a game, or another type of virtual asset. Whether or not that stops people from simply copying an NFT instead of paying for it is besides the point, Chua says.

“You know when you own a piece of land but people keep building houses on it without making paalam? That’s what it’s like,” he explains. “But, dude, at least you own the land title.”

The right click way

“During this party, I was, like, talking to Juancho (Chua) like, ‘Bro, have you heard of this NFT thing?’” Alargado recalls. “It’s, like, so popular, you can parang gamit them for promotion, bro.” Alargado says that he tapped Broarez and Chua, both computer science majors, to help with the project because of their “technological expertise” and the fact that they also joined the cryptocurrency craze since its early days. “Then I guess we thought that we just had to do something about the [redacted] environment. It was no good na talaga, like, grabe.”

These images of distinctly endemic animals have been designed to flaunt the classic conyo regalia. Some of their highest priced NFTs include a tarsier wearing airpods, a Philippine eagle with a hat, and a tamaraw wearing gold chains. Only a limited number of images will be available for sale based on how many animals are left per endangered species.

Against NFTs through NFTs

“I’ve always been passionate about using my expertise in computers for the greater good,” Chua conveys. “That’s why, when Raton (Alargado) suggested that we invest in NFTs, I was agad like, ‘G bro, we can do that for a cause.’”

Although Broarez admits to not being immediately amenable to the idea, “Raton, that [redacted] genius talaga, raised na NFTs and [cryptocurrency] aren’t physical so dein na need mag-print ng more money. Dein na [rin] need ‘yung mga canvas and paint na might be cause for more trash. We’re totally saving the environment, man.”

The existence and continuous circulation of NFTs—as with any cryptocurrency—depends on a rigid and distributed database known as blockchain, which allows a digital asset to remain unique so that users cannot use the same token twice. This is done through a “proof of work” algorithm, and it takes astonishing amounts of electricity to produce.

“That’s exactly why this [redacted] sucks, eh, it’s not good for TRaCo’s branding,” Alargado grumbles. Recently, higher energy consumption that came with the rise of cryptocurrencies have raised concerns from environmentalists. The process of making Bitcoin alone currently consumes around 130 terawatt-hours (tWh) of electricity annually—which is larger than an entire country’s usual energy consumption. In 2020, the Philippines consumed 101 tWh of electricity. Bitcoin’s share in renewable electricity use alone is thought to be around 39 percent to over 73 percent—depending if one listened to Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance or Coinshares.

When asked about this energy-intensive feature of NFTs, Alargado said that TRaCo was exactly their way of raising awareness about it. “You see, bro, those crypto-bros [definitely] don’t listen to scientists about the bad effects, kaya we thought, why not fight forest fires with more forest fires? Besides, NFTs would really get the attention of our fellow Lasallians, dude, diba?”

Broarez confidently asserts that what they are offering is not like the other NFTs. “This isn’t a scam, deins bro, with these sweet NFTs, we have the potential to change the world!”